Scientists discover a unique microbiome on our planet's roof

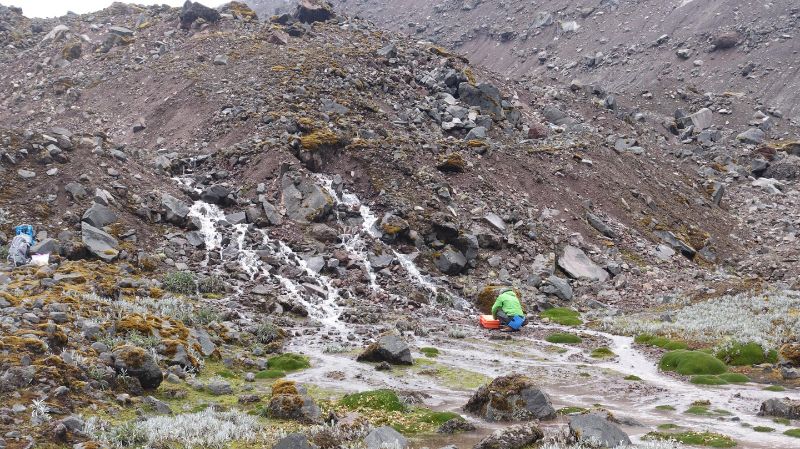

The streams draining the glaciers on our planet’s mountaintops harbor a wealth of unique microorganisms, yet little was known about these complex ecosystems until recently. A team of scientists led by EPFL has carried out an unprecedented study, taking an in-depth look at the microbiome of these glacier-fed streams. The scientists, with the help of mountain guides and porters, spent more than five years collecting and analyzing samples from 170 glacier-fed streams in New Zealand, the Himalayas, the Russian Caucasus, the Tien Shan and Pamir Mountains, the European Alps, Scandinavia, Greenland, Alaska, the Rwenzori Mountains in Uganda, and both the Ecuadorian and Chilean Andes.

The research was led by Tom Battin, a full professor in environmental science and the head of EPFL’s RIVER lab, as part of the Vanishing Glaciers project funded by the NOMIS Foundation. The scientists’ key findings were published in Nature and Nature Microbiology on 1st and 2nd January 2025.

A microbial atlas

Glacier-fed streams are the most extreme freshwater ecosystems in the world, and they all have pretty much the same characteristics: near-zero temperatures, low nutrient concentrations, almost no sunlight in the winter and strong UV radiation in the summer. “Given the extreme conditions in glacier-fed streams, we expected to see low microbial diversity overall with little change from one mountain range to the next,” says Leïla Ezzat, a postdoc and the lead author of the Nature article. “But our analyses proved the contrary – there’s a remarkable amount of microbial biodiversity and biogeography across the world’s glacier-fed streams.”

The scientists drew on their findings to put together the first global atlas of microbes in glacier-fed streams. They discovered a unique microbiome in these environments – one that clearly differs from other cryospheric systems. Interestingly, they found that almost half of the bacteria are endemic to a given mountain range. That was particularly true in New Zealand and Ecuador – regions already known for their high variety of endemic plants and animals. The scientists attribute this to the geographic isolation of mountains – similar to that of islands – and to the natural selection that’s particularly strong in extreme environments like glacier-fed streams. The Nature article also provides insights into the strategies that enable bacteria to evolve in one of Earth’s most extreme ecosystems.

Surprisingly complex

In the Nature Microbiology article, the scientists reported on their analysis of thousands of genomes of bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae and viruses living in glacier-fed streams. Their research revealed just how complex the glacier-fed-stream microbiome is and the many potential biotic interactions it contains. “It's fascinating to see the broad range of adaptive strategies that microorganisms have developed to survive in this extreme environment,” says Grégoire Michoud, the article’s lead author. For instance, these microorganisms have evolved to metabolize a variety of substances – organic carbon, solar energy, minerals and probably even gases – enabling them to draw energy from many different, fluctuating sources.

A biobank in Valais

Both articles were published in early 2025 – which the United Nations have designated as the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation. Preserving our glaciers also means protecting glacier-fed streams and their microbiome – an urgent task given how quickly ice is melting, but also a feasible one. “Having spent the past few years traveling across the Earth’s mountaintops, I can say we’re clearly losing a unique microbiome as glaciers shrink,” says Battin. This has prompted him to call for the creation of a biobank to safeguard this and other vanishing microbiomes for future generations of researchers and for use with next-generation biotechnology. He hopes that such a “safe vault” will be set up in Valais. “Given the skills housed at EPFL’s Alpine and Polar Environmental Research Centre (ALPOLE) in Valais, that seems like a logical place for the biobank,” says Battin.