Finding security flaws in Android ahead of malicious hackers

EPFL researchers in computer and communication sciences are hacking and fixing Android phones before malicious hackers do. They uncovered 31 security critical in the Android system, explored its risks and developed methods to mitigate some of the key ones through better testing and broader mitigations.

“Vulnerabilities in smart devices are the Achilles heel that can compromise the most critical aspects of a mobile device,” says Mathias Payer who leads EPFL’s HexHive Laboratory which conducts research in cyber security. “The main risk is that hackers can get a foothold in your system and gain lifelong access to your data as long as you have the same phone. Your phone is no longer secure.”

Mathias Payer, head of EPFL’s HexHive Laboratory - - 2024 EPFL/Murielle Gerber - CC-BY-SA 4.0

The diverse critical security flaws revealed by the researchers could have been exploited to steal personal information like fingerprints, face data, along with other sensitive data stored on one’s phone like credit card or social security information.

“We studied the Android system because of the open nature of its platform, but similar security flaws are likely present in the iPhone ecosystem as well. We see much less public security research on iPhones due to Apple’s closed approach which forces researchers to first reverse engineer essential information that is publicly available on Android,” explains Payer.

Marcel Busch, a postdoc in the HexHive Laboratory with Payer, spearheaded the efforts into privileged layers of Android together with the PhD students Philipp Mao and Christian Lindenmeier that resulted in three publications presented at this year’s Usenix Security Symposium, one of the world’s four top tier cybersecurity venues. In their work, they show exactly how these security flaws manifest themselves and which layers of the Android system’s architecture are affected.

The details of the Android security flaws over three layers

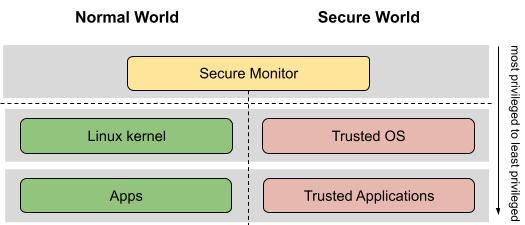

The Android system essentially processes information via three layers of code (iPhone’s iOS follows a similar architecture.)

The first layer is the secure monitor, it’s the code that processes switches to and from the world of encrypted data known as the secure world. The second layer is divided into two parts, the secure world where sensitive data is encrypted, and the normal world built on a Linux kernel. The third layer builds on top of the second layer and contains all the apps. Day-to-day apps, like the photo app or messaging app, in the normal world talk to secure apps called Trusted Applications (TA) such as the key master app which manages cryptographic keys or the biometric information management app that contain sensitive data about the user running in the secure world.

2024 EPFL/HexHive Laboratory - CC-BY-SA 4.0

Numerous defects and vulnerabilities discovered

The EPFL team discovered security flaws across all three layers of the Android system. The researchers developed a program (called EL3XIR) that essentially throws unexpected inputs at the target code to reveal software defects and vulnerabilities, a technique called fuzzing. EL3XIR revealed 34 bugs in the most fundamental and most privileged layer of Android security, the secure monitor level, of which 17 were classified as security critical (the most severe risk level).

The researchers also revealed a confusion in how the Android system communicates with trusted applications. The confusion arises when information from trusted applications are mislabeled when processed between layers. In particular, the complex and critical interaction between accessible day-to-day apps and trusted applications that has to go first down through the secure monitor, and then back up through the secure world and into the trusted applications is affected by this issue. Across 15,000 trusted applications that the team analyzed, the researchers discovered 14 new critical security flaws, uncovered 10 silently fixed bugs that vendors patched without notifying users and confirmed 9 known bugs.

Mathias Payer, Marcel Busch and Philipp Mao from the HexHive Laboratory - 2024 EPFL/Murielle Gerber - CC-BY-SA 4.0

They also discovered that, if vendors did not update the Android system properly with secure patches, then hackers could force a downgrade to previous vulnerable versions of trusted applications and retrieve sensitive information, compromising the entire Android ecosystem throughout the three layered architecture. The researchers scanned over 35,000 trusted applications deployed across numerous phone manufacturers.

“Android is a complex ecosystem with many different vendors and devices. Patching security vulnerabilities is complex,” says Mao, PhD candidate with the HexHive. “We followed industry standards by responsibly disclosing all our findings to the affected vendors and gave them 90 days to develop patches for their systems – which they did – before publishing any details. The insights from our findings and our automated tooling will support securing future systems.”

What’s the bottom line for the consumers? To keep their system and apps up-to-date by installing updates whenever they become available, to download apps only through trusted app stores and to buy a device from a manufacturer that guarantees long update cycles. Busch observes that “for some of the manufactures we studied, time-to-market is the key metric which doesn't leave much room for the diligence required for building secure systems.”