Why it will be imperative to reduce the size of rental properties

The thesis research, performed by civil engineering student Margarita Agriantoni, is based on computer simulations of different housing development scenarios over the next 30 years (from 2020 to 2050). Her findings come as a stark warning to both the owners and tenants of residential dwellings: if we want to significantly reduce Switzerland’s housing-related energy use, the entire industry needs to rethink its practices, from the way homes are designed and built to how they’re used.

Around 58% of Swiss households rent their homes. The average dwelling surface of these homes has risen steadily over the past few years, as has the floor area per capita – a metric correlated directly with a building’s environmental footprint. Nowadays, a 100 m2 apartment, for example, is constructed or heated the same way if it is intended for two or four people. “Floor area per capita is the key figure we need to reduce over the long term in order to achieve more sustainable housing,” says Agriantoni. “But the trend today is actually going in the other direction. That’s especially problematic in a country like Switzerland where both the population and the demand for housing are growing constantly, but residences are getting harder to find.”

Agriantoni’s thesis was supervised by Prof. Philippe Thalmann at EPFL’s Laboratory of Urban and Environmental Economics (LEURE), within the School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering (ENAC), and is part of a cross-disciplinary project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). The project also draws on research conducted by EPFL’s Laboratory on Human-Environment Relations in Urban Systems (HERUS) (see EPFL news article from 9 September 2021) and the ETH Zurich Chair of Environmental Systems Design (ESD).

11,000 apartments under the microscope

Agriantoni and her colleagues created a housing-development model that incorporates technical as well as sociological factors. It draws on data from 11,000 apartments in buildings across Switzerland. The buildings are a mix of private-sector dwellings, owned by Swiss insurer La Mobilière, and dwellings owned by two housing cooperatives: ABZ in Zurich and SCHL in Lausanne (Société Coopérative d’Habitation). This mix is an important feature of her research because the two types of owners build and manage their properties in different ways.

The first step in developing the model – which could eventually be used in other European cities – was to compile a database of detailed information about the properties, such as land price, surface area, rents charged, and any renovation work completed. This step took one year. “I held several meetings with the property owners in order to understand their investment strategies and management processes,” says Agriantoni. The next step was to collect information about the tenants, and for this a tenant survey was conducted in which 1,000 households responded to a questionnaire, providing data about their household composition and size and how satisfied they are with their current dwelling. The goal here was to get a better picture of who lives in the apartments and how they use the space.

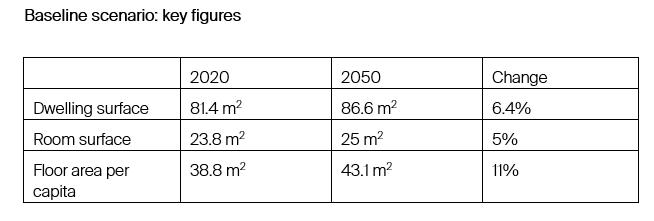

The researchers used the data from these two steps to create a dynamic, agent-based model that corresponds as much as possible with actual conditions. Agriantoni ran the model to simulate a range of scenarios reflecting different decisions by property owners and tenants over the next 30 years. “We first came up with a baseline scenario, which indicated that the average floor space per capita will grow by 11% between now and 2050,” says Agriantoni.

In addition to the baseline scenario, she ran four other scenarios to see if the trend in floor space use could be reversed by adjusting some of the variables. In the first scenario, property owners introduce stricter rules on the number of tenants. In the second, property developers focus on renovating and exploiting existing buildings rather than constructing new ones. The third scenario is a combination of the first two. And in the fourth scenario, tenants gradually become more sensitive to environmental issues and therefore take the initiative to live in smaller dwellings. The third scenario turned out to be most effective, but in each of them, the floor area per capita increased over time, albeit at a slower rate than in the baseline scenario.

Broader awareness of environmental responsibility

What does all this mean for achieving our sustainability goals? “A concerted effort will be required on the part of both property owners and tenants,” says Agriantoni. “Increasing tenants’ environmental awareness will be crucial, but it’s not so easy in practice. Getting people to choose homes that are better suited to the size of their families – but without sacrificing their quality of life – will be just as important as encouraging them to cycle to work instead of driving, for instance.” Property developers must also change their construction habits. “Reducing the surface area by even just a few square meters can have a real impact,” she adds. “But more broadly, society as a whole needs to rethink its value system whereby bigger is automatically believed to be better.”