Monograph explores a vibrant quarter-century of architecture in Vaud

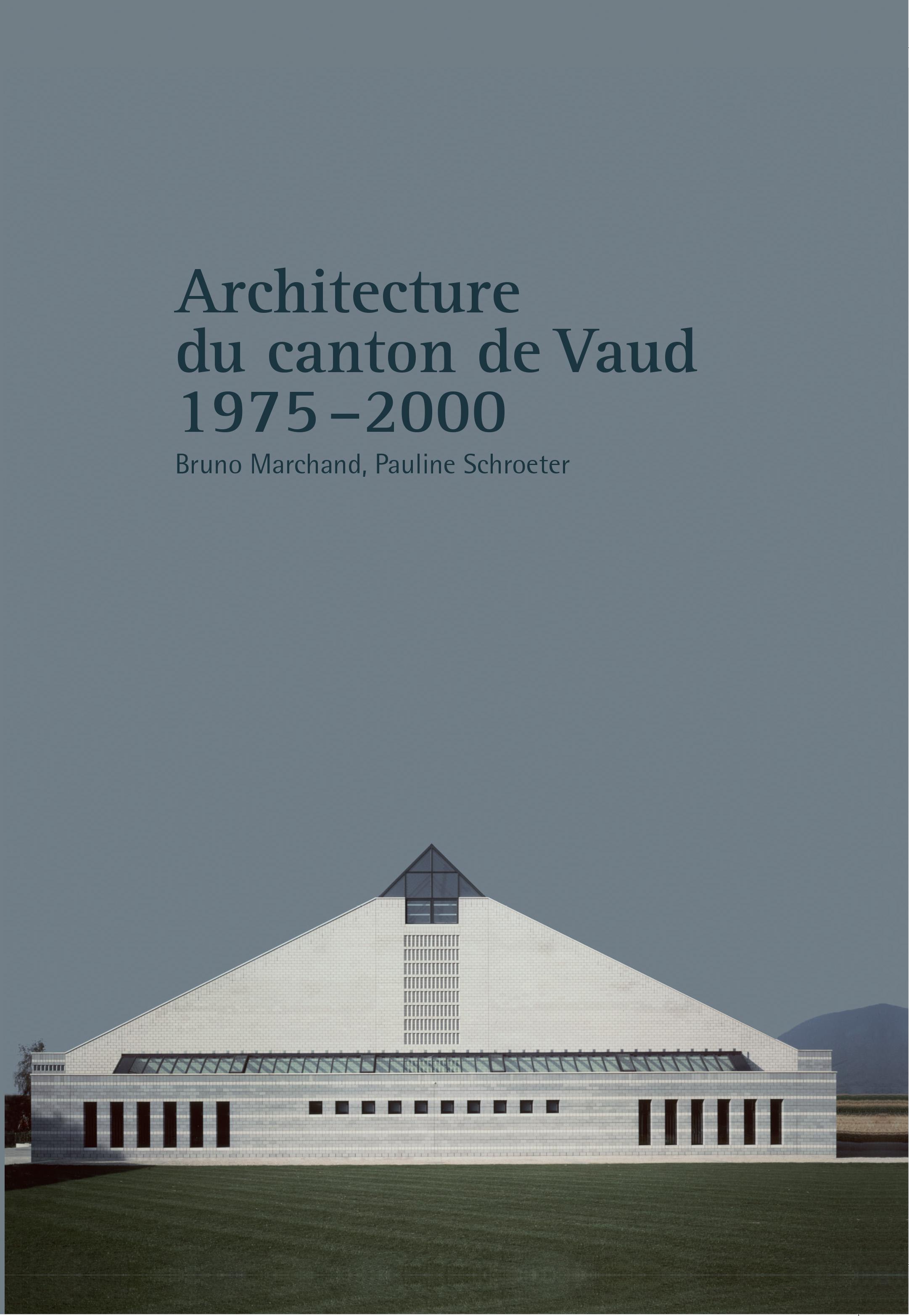

A wine-grower's hut, a transformer substation, a 250-unit housing estate, a high-school, a wood-fired boiler room, an arsenal, a church and a prison. Dozens of building renovations, transformations, refurbishments and redevelopments – not to mention new town squares, roads, lakefronts, footbridges, stairways and elevators. And finally, the expansion of three major universities: University of Lausanne (UNIL), EPFL and Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV). This in a nutshell is what’s covered in a new book by architects Bruno Marchand, professor emeritus at EPFL, and Pauline Schroeter, an EPFL scientist. Across nearly 500 pages, illustrated with both black-and-white and color photos, the authors present a quarter-century's worth of architectural gems in the Canton of Vaud. We sat down with them for an interview.

Why did you choose this particular time frame?

BM: Our book is a continuation of an earlier one we wrote on 1920–1975. The mid-70s was a time of great upheaval, particularly in the wake of the oil crisis and the end of modernism in the architectural world. 2000 was mostly a symbolic year, but nevertheless meaningful, as it marked the end of the effects of the real-estate market crash in the mid-1990s.

Bruno Marchand, EPFL professor emeritus. ©DR

What did you discover as you did your research for this book?

BM: A surprisingly large number of architectural projects! My professional career began in 1980, and I was under the impression that not much was built during this time. Instead I discovered that – unlike during the period covered by our first book, when most construction took place in large urban areas – this time many structures were built in the suburbs and elsewhere. Especially after highways started to arrive in 1964. A second surprise was that there was an equally large number of conversion and renovation projects, for either older buildings or those from the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s.

What most characterized the period covered in your new book?

BM: We basically saw three separate phases corresponding to the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. The first was a genuine time of crisis, but very interesting because it signaled the advent of several new societal issues such as environmental awareness, heritage preservation and a concern for energy efficiency. The ‘80s were dominated by projects to build large institutional buildings and facilities, notably schools. This period can be characterized as postmodern, with a renewed focus on history and monumentalism and a return to a certain independence – architecture shook off the influence of other disciplines. It was also a time that saw a proliferation of public RFPs. During the ‘90s, commissions fell off due to the slump in the real-estate market. Spending was reined in, and we began to work more simply, often with only a single material. At the same time, artwork started to play a more important role in architectural projects.

What criteria informed your choice of which projects to include in your book?

PS: As for our previous book, we searched through local, national and foreign architectural magazines, which provided us with a fairly substantial pool of material. We also consulted various archives, architects’ monographs and the websites of architectural firms, since many of them are still active today. Then we selected those projects that were representative of a given movement, whether due to their architectural style, their vision or the issues they reflected.

Pauline Schroeter, scientific collaborator at EPFL. © DR

Which architectural projects stood out to you?

PS: Vincent Mangeat's high school in Nyon, the Ecole de la Construction in Tolochenaz by Patrick Mestelan and Bernard Gachet, and the Chéserex community center by Fonso Boschetti. In addition to their architectural authority, these buildings express very different ideas of what an “institution” is. There were two other projects that also received a lot of attention: the Telecom PTT building by Rodolphe Luscher, adjacent to EPFL; and the Vaud Cantonal Archives by Atelier Cube.

What about noteworthy renovation projects?

PS: We made a distinction between renovations of historical buildings – such as Lausanne's Galeries du Commerce, which was converted into the Lausanne Conservatory by Longchamp Froidevaux – and what we call “modern legacy works,” which include, for example, Nestlé's headquarters in Vevey, which was renovated by Jacques Richter and Ignacio Dahl Rocha.

What distinguishes Vaud’s architecture from that in the rest of French-speaking Switzerland? Or even Switzerland as a whole?

BM: Several books and articles were written between 1975 and 2000 on the distinctive features of regional architecture. However, even though we can identify clear differences between Vaud’s architecture and that of Geneva, we generally tend to compare the whole of French-speaking Switzerland with the German-speaking part. The former is influenced by France and the latter by Germany. But we shouldn’t be overly schematic – since 1973, visiting professors at the School of Architecture have been identified only as national or international. Students now are constantly exposed to international trends, and this somewhat weakens the more traditional local influences. Moreover, regarding postmodern architecture in Switzerland, there's no doubt that its birthplace was the French-speaking part. But today you could say there’s an architectural style in – but not of – French-speaking Switzerland.

Did you find that architects preferred to use certain materials?

BM: Yes. Amazingly, we found an overwhelming use of sand-lime brick in the 1980s. This material appeared in every type of structure, overturning the idea that each material was associated with a specific use. Rarely in the history of architecture have I seen a material that was so popular at a given moment in time. Although sand-lime brick possesses a lot of advantages, I think it was a passing fad. Wood and concrete made a comeback in the ‘90s.

What were some key trends in terms of renovations and restorations?

BM: A successful renovation project marries the old with the new. It respects a building’s architectural heritage while leaving room for a more contemporary, creative statement.

Your book devotes a chapter to three major university campuses, including EPFL’s. What was noteworthy about EPFL’s expansion?

PS: Our book begins with the completion of the campus' initial planning phase. The design for this phase had a horizontal, east-west orientation, and was criticized as being inward-turning, grey and somewhat austere in its architecture. The second phase therefore represented a departure from that, with buildings set at a 45-degree angle in order to allow for a wider range of uses. Next was the construction of the plasma physics research center (out of sand-lime brick) in the campus’ southern area – the cornerstone of what later became the technology park. The third phase, in the ‘90s, took place in the campus’ northern area and attempted to unify the earlier phases by adopting the same building orientations as the earlier phases; some of the buildings ran east-west and others north-south along the diagonal axis, with the square in front of the SG Building as a focal point.

One final question: you express concern about the lack of cultural dialogue in architecture today, as well as architects' misgivings about public discussions. Is architecture experiencing a moment of uncertainty?

BM: Every period is a bit different. For the past two decades, architects have been busy building and have had little time to reflect more broadly on the profession or to devote to political engagement. Our profession has also become increasingly complicated due to technical constraints – and this sometimes causes architects to think more inwardly.

© EPFL PRESS